Sports Sponsorship Dissertation Sample - Review of Literature

- Andrew Fitzsimmons

- Aug 20, 2018

- 12 min read

Updated: Dec 13, 2018

A review of literature surrounding sports sponsorship submitted as a BA Honours dissertation. Full title: ‘Have stadium sponsorship deals become as influential as shirt sponsorship at increasing purchase intentions of UK football fans’?’

Chapter 3 - Review of Literature

2. 0 - Introduction and Overview of Marketing Communications

This chapter presents a review of literature providing a background of sponsorship and the role it plays as a marketing communications tool.

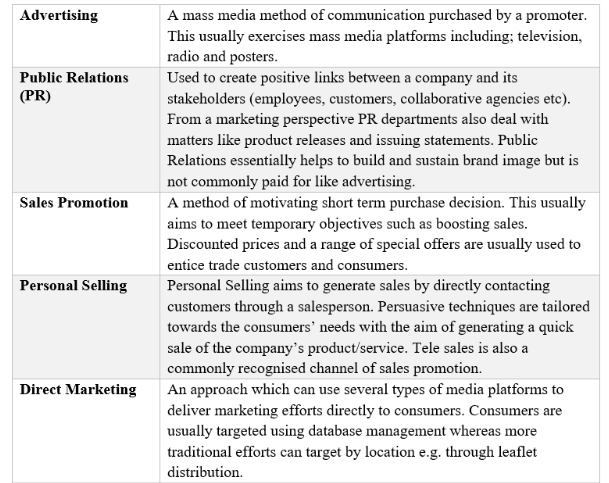

Essentially marketing communications attempt to connect with consumers in order to manipulate their awareness, opinions and behaviour to benefit the marketer (Lagae, 2005). This can be achieved through a variety of tools. Shimp and Andrews (2013) subscribe to the idea that public relations, advertising, direct marketing, sales promotions and personal selling are the commonly established communications tools. Additionally, Jobber and Ellis-Chadwick (2016) acknowledge a more modern tool relating to ‘digital promotions’. Each traditional element and function within the communications mix is shown in table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Promotional Mix Elements

Source: (Shimp and Andrews, 2013; p. 8-9)

For the purpose of this study, literature narrows towards sports sponsorship. An in-depth look at stadium and shirt sponsorship is shown through the gathered secondary figures and research. This aims to provide an understanding of the growth in prominence and value of two major methods of sponsorship within sport. Literature surrounding sponsorship success is also reviewed with a focal point on how buying behaviour can subsequently be impacted by such communications.

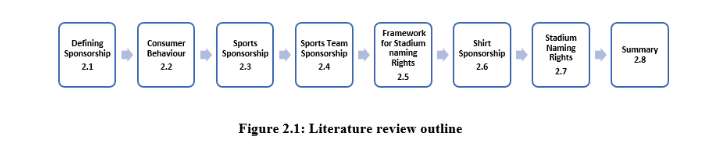

The remainder of this chapter has been split into 7 sub-sections as shown in Figure 2.1.

2.1 - Defining Sponsorship

Sponsorship can be traced as far back to ancient Greek and Roman times (Meenaghan, 1998). Its origins lie in Athens where those who invested money to sporting events would be rewarded by having their names engraved in marble (Medcalf, 2008). Recent sponsorship is much more commercialised and plays a significant role within marketing communications. In its simplest form modern sponsorship is described by Lamont (2011) as a mutual exchange between two partners who will both benefit from the agreement. Fill (2013) expands on this by suggesting the sponsor targets a certain audience though association in exchange for resources such as financial payment.

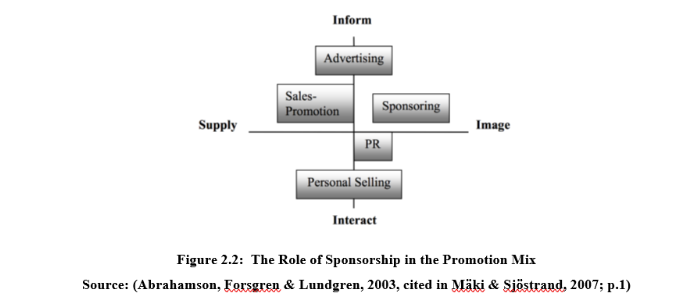

Fill (2013) acknowledges that there has been confusion surrounding which area of the communications mix sponsorship falls under. Although more commonly associated with public relations, the author feels sponsorship’s primary goal of raising awareness better positions the tool as a method of advertising. Figure 2.2 presents the position of sponsorship within the promotional mix.

Sponsorship is one of the most common yet immeasurable tools within marketing (Cornwell et al. 2005). Despite effects being harder to calculate than more basic tools such as personal selling, Nickell et al., (2011) feel there are many benchmarks which sponsorship success can be measured against. Awareness receives a lot of attention by academics such as Hickman (2015). However, sponsorship provides attributes supplementary to basic awareness. Other objectives include increasing visibility, competitor differentiation and deepening relations with current and potential customers (Clow and Baack, 2016). Akhtar (et al.,2016) draw attention to sponsorship’s effect on brand image. Clow and Baack (2016) support this stating that enhancing brand image is a key sponsorship objective. Imagery created by sponsorship is mostly built upon the foundation of the ‘meaning transfer theory’. Jobber and Ellis-Chadwick (2016) describe sponsorship as providing four main opportunities as shown in Table 2.2.

Brand awareness is one of the main benefits of using sponsorship. This is generated by exposure of an appropriate message to the correct target audience in the correct place. Exposure is seen as fundamental to modifying consumer perceptions and beliefs (Evans et al. 2009). To illustrate, a study by Bennett (1999) tested recall of fans of London based sports teams compared with a control group. The study found that the fans’ purchase intentions towards sponsor brands they recognised was significantly higher. It is further suggested that long-term association between two parties results in longer lasting brand awareness and recall (Mason and Cochetel, 2006).

McCracken’s (1989) ‘meaning transfer theory’ provides a theoretical approach towards the transfer of image. As outlined by Grohs et al. (2015) brands can frame their image by reflecting off an associate. This includes mirroring aspects such as the character of the sponsored entity (Smith, 2004). Heider’s (1958) ‘balance theory’ can also accommodate sponsorship. This propositions that if a positive attitude is held towards the entity it will transmit onto the sponsor (Roy et al. 2012). These frameworks both build on the concept of image reflection but in retrospective ways. The ‘meaning transfer theory’ proposes that brands should be striving to find entities which possess the personality aspects they desire. For instance, Tag Heuer aimed to gain an athletic and exciting positioning as a result of sponsoring the McLaren Formula 1 team (De Burton, 2004).

2.2 – How Marketing Communications Influence Buyer Behaviour

Consumer behaviour can be construed as the actions people take when purchasing, using and disposing of products/services (Blackwell et al., 2005). An understanding of consumer behaviour is essential to businesses whose main objective is to lure consumers towards their goods and services. The better the understanding, the easier it is for them to tailor marketing communications towards achieving this goal (Clow and Baack, 2016). The goal of sponsorship is dependent upon the brand’s intent of use. However, Lagae (2005) argues that sport sponsorship rarely communicates more than a name and logo. Discordantly, as shown by Tag Heuer (De Burton, 2004) many sponsoring brands contradict this with much focus being placed upon building image as opposed to basic awareness.

Understanding behaviour is vast in complexity, resultantly many models have been developed to provide a greater understanding of how consumers process communications. Frameworks applicable to sponsorship’s impact on consumer behaviour are minimal, however, many aspects of advertising can also be applied to sponsorship as shown by the hierarchy-of-effects and AIDA models displayed in table 2.3.

It is generally accepted that consumers move through a three-step process when making purchase decisions (Clow and Baack, 2016), as shown within both models in figure 2.3. Cognitive, affective and behavioural also known as “think, feel and do”, provide a sequence of steps consumers travel through when stimulated by marketing activities (Lagae, 2005, pp.15).

The cognitive element consists of the mental awareness and comprehension one has of a subject, topic or brand, essentially built through brand awareness and visibility (Sreejesh et al., 2014). During this stage brand awareness and recall are valuable in shaping favourable cognition (Lagae, 2005) as consumers cannot hold feelings towards an unknown brand. Sponsorship promotes brands and puts company logos into the eyeline of consumers.

The affective element refers to the basic feeling and perception then held towards the subject (Clow and Baack, 2016). Sponsorship aids this process through the previously mentioned ‘image transfer’ and association. Correspondingly, negative views towards the sponsorship method or sponsored entity anticipates that negativity will also be transferred. As Sreejesh et al. (2014, p.122-123) state feelings can be “favourable or unfavourable” and can entice emotion ranging from “anger” to “happiness”. This consequently has an impact on future buying behaviour (Sreejesh et al., 2014).

Finally, the behavioural stage refers to the action that the consumer undertakes; which relevantly could be an intention to purchase (Clow and Baack, 2016; Lagae, 2005). The process suggests that the behavioural stage is somewhat instigated and dependent upon positive transition through prior stages. In essence, consumers must first possess favourable awareness and knowledge of a brand. A liking and preference over competitors then develops an intent to purchase.

2.3 - Sports Sponsorship

Global spending on sponsorship has grown annually in the last 10 years (2007-2017). It is expected that a total of 62.8 billion dollars will be spent worldwide on sponsorship in 2017 (Statista, 2017). This is unsurprising as sponsorship accounts for 22% of communications budgets (Sneath et al., 2006). Within this, sport sponsorship amounts to nearly three quarters of all expenditure, as shown in figure 2.3.

Jobber and Ellis-Chadwick (2016) believe that sports sponsorship is undoubtedly the most useful sponsorship platform for a variety of reasons. Perhaps most significantly sport can communicate globally with all cultures and languages. It is also recognised that sponsorship embeds itself within viewing, rising from marketing clutter (Kotler and Keller, 2009). This providing an advantage over other communication tools. In addition, sport allows for targeting of a specific and refined audience (Ferrier, 2013). For example, Budweiser’s sponsorship of the FA cup effectively reached their demographic of young males (Reynolds and Charles 2011).

Sports sponsorship in general can provide many transferred values to the sponsor. Values associated with sport relate to health, excitement and action (Jobber and Ellis-Chadwick 2016), desirable to many brands. Due to the popularity of modern athletes it could be said that sport sponsorship builds upon image transfer in a way similar to celebrity endorsement. While this may be true within sport in general, Barreda-Tarrazona (2011) found image transfer is less effective within football. In response, the long-term nature of football stadium sponsorship could be the answer to improved image transfer. Pitts and Slattery (2004) derive the opinion that cognitive response to sponsorship is positively boosted by duration. However, there are many factors which support that sponsorship effectiveness is harder to achieve in football than most other sports; such as team identification and sponsor fit.

2.4 Sports Team Sponsorship

2.4.1 Team Identification

Team identification or ‘attachment’ refers to the emotional connection an individual has towards a sports team (De Amorim and De Almeida, 2015). A study by Koronios et al. (2016) on Greek football found that fans with a deeper connection to a club held a better image of their sponsor. Additionally, it was found that fans held a desire for the brand’s products even if they were uninterested in the product category. The strength of team identification has also been shown to overcome aspects such as team performance in creating a purchase intention (Heidi et al., 2011).

It is apprehensible that whilst fans want to see their own team achieve, they also take pleasure in rival team failure (Grohs et al., 2015 cited in Leach et al., 2003). In correlation, a study of German football fans found that negative views of a sports team directly translated to negativity towards their sponsor (Grohs et al., 2015). Duarte et al. (2017) highlight the strong sense of group identification within football as reasoning for this. This idea is illustrated by the case of Vodafone who suffered a dramatic decline in sales within a major UK city as a result of sponsoring a team from a rival area (Grohs et al., 2015 cited in Schlesinger 2010). Further, the extremity of team rivalry within Scotland culminated in Celtic and Rangers holding a joint sponsor for several years (Grant, 2013). Sponsors clearly felt that the intensity of the rivalry meant associating with one team would alienate the brand to the other club’s supporters.

2.4.2 Perceived Fit

As mentioned earlier image transfer plays an important role within sponsorship. Chen and Zhang (2011) express that many studies focus on the perceived fit/relevance of a sponsor to a sponsored entity as an important factor in ‘consumer acceptance’. The authors use the example of ‘Papa John’s’ being a largely accepted sponsor of the Louisville Cardinals as they are both based within the same city. Woisetschläger et al. (2014) supports this idea of regional identification being affective in reducing fan resistance. The tribal nature of sports teams can make outside sponsor’s appear as a threat to club’s tradition, especially influencing club traditions such as stadium names (Woisetschläger et al., 2014). Abosag et al. (2012, p.1248) portray this summarising that;

“by showing concern and due respect for the club’s heritage and traditions, supporter’s concerns over the commercialisation of the club can be neutralised.”

2.5 Theoretical Framework for Stadium Naming Rights

Chen & Zhang’s (2011) framework (figure 2.4) provides a theoretical approach evaluating the effect stadium sponsorship has on fans’ attitudes to attend games and purchase from a sponsor brand. Relevantly, this model incorporates previously mentioned factors such as perceived fit and team identification. As the model suggests, there are a number of intertwining issues which effect consumer attitude’s to purchase. Furthermore, where most studies focus on the benefits of sponsorship, Chen and Zhang (2011) consider that negativity can also be accustomed. Lacking focus towards sponsorship negativity from other academics makes this model all the more relevant and applicable.

Figure 2.4 - Theoretical model for naming right sponsorships

Sourced: (Chen & Zhang, 2011; p. 113)

2.6 - Growth and Extent of Shirt Sponsorships

The evolution of shirt sponsorship can be seen through the transition from local to global sponsors. Such extent has resulted in calls for tighter regulations; for example, government actions restricting those who can sponsor.

There is some debate surrounding the first on-shirt sponsorship deal. Allen (2014) credits Uruguayan club Peñarol during the 1950’s with the honour. Conflictingly, Riche (2017) reports that it was not until Kettering Town were seen bearing the name of a local tyre manufacturer in 1976. Unarguably, the evolution of shirt sponsorship was sparked in 1973, when German club ‘Eintracht Braunschweig’ accompanied their strip with the logo of now globally recognised brand ‘Jägermeister’ (Merkel, 2012). Simultaneously, Eintracht and Kettering both faced opposition with governing bodies demanding that sponsors must be removed. Prevalence resulted in a loosening of restrictions and shirt sponsorships subsequently surged across the globe (Allen, 2014). Interestingly, Riche (2017) finds that not until 1983 were clubs allowed to display shirt sponsors in front of television cameras. The next decade saw the introduction of the now known ‘Premier League’ coupled with the rise of replica shirt sales (Riche, 2017). This enhancing reach and visibility, attracting global investment.

The rise of shirt sponsorship has been matched by the growth of investments. Figures show that shirt sponsorships in top European leagues doubled between 2000-2011 from 235 million to 470 million euros (Allen, 2014). Globalisation is apparent within UK football as Miller’s (2017) research shows that only 4 out of 20 English Premier sponsors are UK based. Manchester United are the main beneficiaries, gathering £47 million annually from American based ‘Chevrolet’.

In the same way clubs appear to snub home-grown talent for international stars it is being reflected onto sponsorship with the demand for globally recognised partner companies (Hess, 2015). In connection, Groves (2011), feels clubs are harming ties with their local communities in order to satisfy markets across the globe. In compliance, figures clearly make it hard for club owners to resist. For example, Barcelona shunned their agreement with charity ‘UNICEF’ in order to sign a more lucrative deal amidst growing financial power (Allen, 2014). While this could be seen as unethical it is clear that many clubs underpin income as their primary responsibility. Another ethical issue caused by financial motivation concerns betting firm sponsors. There has been political pressure put upon the prominence of betting firms within football, with 9 out of 20 English Premier clubs associating with gambling sponsors. It is also stated that they are doing little business within the UK and are using the global appeal of the Premier league to allure international customers (Davies, 2017). MacInnes (2017) develops this through the example of ‘Fun88’, an Asian focused gambling site and current shirt sponsor of Newcastle United (nufc.co.uk, 2017). As Miller (2017) states there is a “blanket ban” on betting within football, making many question its appropriateness. Clearly, financial power is playing an increasing role. It could be argued that shirt sponsorship has become a saturated method, subsequently focus is being placed on emerging efforts, hence, the rise of stadium sponsorship.

2.7 - Growth and Extent of Stadium Sponsorships

Academic research concerning stadium naming rights is severely lacking, making this study of greater importance. However, growth can be shown by its current prominence and income generated.

Stadium sponsorships within sport can be traced to the naming of Chicago Cubs’ “Wrigley Field” almost a century ago (Stegelmann, n.d.). The commercialisation of American sport makes each game a marketing goldmine. None are more extreme than the NFL Superbowl with an estimated 103 million worldwide viewers watching the 2018 event held in the appropriately named ‘U.S Bank Stadium’ (CBS, 2018). However, stadium naming needs to be looked at on a more serious level. For instance, Schalke 04’ currently hold an agreement with a brewing company for the rights to hold their stadium name and exclusively sell their product (Stegelmann, n.d.). This understandably creating a two-way relationship with fans. Contrastingly, Real Madrid’s decision to sell naming rights of their world-renowned arena to a petroleum investment organisation is likely to leave fans bewildered. This is also demonstrated within the UK with the emergence of stadium names including Dumbarton’s; Cheaper Insurance Direct Stadium and Livingston’s; Toni Macaroni Arena (Moore, 2015).

Where there is a history of stadium sponsorship within the US, its emergence within Europe is more recent. Stegelmann (n.d.) finds that there are around 170 naming right deals across the top two divisions of UEFA’s member nations, thus, generating around two thirds more income than that of 10 years ago. In 2017 it was found that only a select few English Premier clubs had not succumbed to the temptation of stadium renaming. These were largely identified as clubs with historic pasts where some facilities had stood for over 100 years (Bernardini, 2017). Thus, illuminating the idea that tradition is a main deterrent of stadium renaming. To illustrate, Tottenham are actively seeking a stadium sponsor for their new stadium opening for the 2018/19 season (Short, 2017), despite having never held a sponsor at their previous ground. Undoubtedly, owners look to recoup some building costs through this however the issue of tradition is apparent. A new stadium brings new tradition; therefore, clubs are clearly taking advantage of stadium sponsors during this time in order to minimise fan resistance. For example, both Arsenal and Manchester City walked into sponsored stadiums (Short, 2017), moving from venues steeped in tradition. Afore-mentioned resistance can also be shown by Newcastle United’s St James’ Park (Previously Sports Direct Arena). Fans staged boycotts of the renaming to the current owner’s company with the main feeling of lost identity. One fan summarised feelings stating;

"Newcastle United and St James' Park are together like black and white, do you want me to cut my vein and show you?" (BBC, 2011).

2.8 - Summary

Findings from this review of literature show the extent of sponsorship within modern marketing. Additionally, the illustration of the recent growth of shirt and stadium sponsorships provides a deeper insight into the rationale of this study.

The main theme surrounding stadium sponsorship is the apparent intrusion of club history and ‘tradition’. On the other hand, shirt sponsorships appear more commonly accepted having fought off opposition in the past. The issue of brand fit and ethics has also been illuminated, with this possibly playing an important role in sponsorship acceptance. These highlighted themes will provide a basis for research and build context to research findings. The illustration of the cognitive, affective and behavioural elements of communication processing is one which will consequently be built upon along with other salient themes.

Comments